Syllabus Reboot: Level up Learning through Friction-free Design

As the fall semester fast approaches, I have turned my attention this week to the journey ahead, planning out grading cycles, downloading rosters, and re-visiting the foundational treatise of any and all college classes: the course syllabus. I remember, years ago, the first time I truly confronted the vast expanses of terra incognita (so much of it cut and paste and not even read by me) in my own syllabi. Since then, I have rehashed this document so many times, year after year, always wondering where to go next. I even signed up for a nine-month professional development series last academic year called “The Syllabus Project” which is informing this year’s re-design. That’s how much I think about the syllabus.

I think about it so much because I know how important it is. It’s not only a guide to my course, but a guide to me, my values, and my highest aspirations for my students. But when I look over those old syllabi–and, truth be told, the remnants still extant in my current ones–I wonder what I am truly communicating to my students with staid, bureaucratic phrasing, and endless bullets of rules and regulations. What might a student come to understand about me, my course, or the relevance of a college education from this text?

I am also reminded of a key concept in product design called “user friction.” This is the amount of “friction” (or “pain points”) an end-user faces when trying to navigate a product, service, or website. You are likely quite familiar with this concept in your own life. Think about the last time you had to pay a past due bill and couldn’t find where on a website to do it while you were bombarded with pops ups, ads and irrelevant information (or there was no website, and you instead had to write a check, find a stamp, and send it off). It’s frustrating, exhausting, and demotivating. And the feeling lingers. Put simply: increased friction means less engagement. And if our goal is to get students to read the syllabus maybe we should consider how to reduce the user friction so they can get more out of their learning.

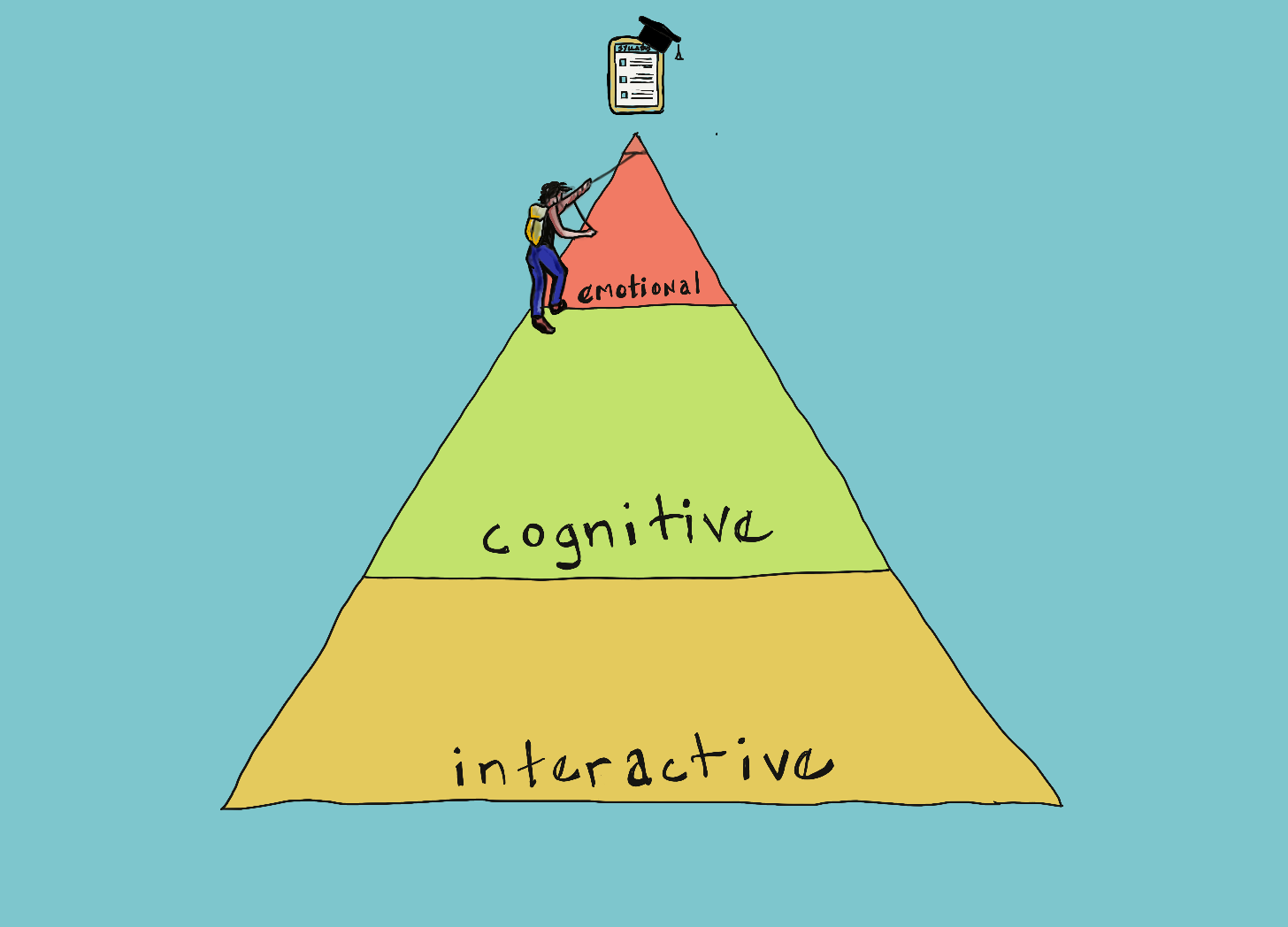

Sachin Reiki, in his Medium article The Hierarchy of User Friction, outlines three “types”: interactive, cognitive, and emotional. These three categories are helpful in framing small tweaks you can make that will revolutionize your syllabus and the way students engage with your course from Day 1.

Interactive Friction

We know bad design when we see it. Walls of text, cluttered imagery, small type, inconsistent use of formatting. All of these make navigating a sea of information more difficult. They are also examples of “interactive friction.” I’m certainly guilty of putting function over form when drafting procedural documents but the syllabus can be more than just the sum of its parts. It can be an extension of departmental branding/recruiting, it can be a toolkit for academic success, a site for unlearning and deconstructing systems, a manifesto of your personal and professional ethos. But it can be none of these things if it is not user-friendly.

In order to lessen this type of friction, the old communication adage applies: know your audience. What does a student want from a syllabus in the first place? Pertinent, succinct, and useful information about the course they have signed up for. They are probably most interested in:

Required purchases (textbooks, materials, technology)

Number and type of assignments (and when/how to turn them in)

Assessment criteria and how their final grade with be calculated

Late work and absence policies

Free campus resources (tutoring, writing center, food bank, childcare, counseling, etc.)

This is what they’re skimming for on Day 1. We instinctively know this, and so often provide subheadings, bullets, or other typographical emphasis to direct the eye toward the most useful info. But what else can we do to smooth the student's path through the forests of our syllabi?

Here are some fresh approaches.

Create Visual Interest

Visuals are especially impactful for a generation reared on smartphones and iPads. Here is the first page of a visual syllabus I used for several years.

I was inspired by Tona Hangen’s “Extreme Makeover” of her U.S. History syllabus that made the viral rounds over a decade ago. I’m particularly enarmoured by her “how to take this course” section:

Reduce Length

There’s no way around this one. Our syllabi are just too long. Rebecca Schuman for Slate regards “Syllabus bloat” as “a textual artifact of the decline and fall of American higher education” replete with “transparent ass-covering and bad intentions.” Consider providing high-level information by highlighting the core components of your course (for example, through a screencast walkthrough, a “highlight reel” of 2-3 pages, or Twitter/X thread).

Create a Roadmap

Let’s imagine that you cannot reduce the length of your syllabus (perhaps you have a master syllabi that is mandated). One way to work with this constraint is to create a “roadmap” of hyperlinks or bookmarks that still highlight the most important information:

Cognitive Friction

When cognitive load is high (while performing a task such as internalizing a lot of information at once) - it causes strain on working memory and this mental effort results in disengagement. A good way to think about this is through “user journey” mapping - how many paragraphs, sections, or pages does the user need to go through to get to the goal of understanding the course and their role in it?

One way of reducing cognitive friction is to chunk the information. Think about ways you can distill and distribute key pieces of information.

Here is another example using the Notion platform (which is free):

Emotional Friction

“Emotional friction” occurs when users feel emotions that prevent them from accomplishing their goals. These could be fears, self-doubt, or shame (or a host of other feelings) and they are sometimes hard to discern. Understanding the aspirations, goals, dreams, mindsets, and backgrounds of students can help anticipate some of these potential barriers.

So much about college is confusing. You have the opportunity, and the obligation, to make things a little easier on your students. Clear is kind, as they say.

Here are four key questions to ask yourself when thinking about how to reduce emotional friction for your students with your syllabus:

What is the true purpose of your course?

There has been a lot of research done into what makes for a happy, successful life. When it comes to work, purpose seems to be the determining factor in whether we find our careers fulfilling or not. “Purpose,” to use Bill Damon’s definition, means that an activity is both meaningful and contributes to the world. Our students want to do well in our courses but above this, they want to do well in their lives. So, it’s worth thinking about what you are really hoping students take away from your course when the final grade is posted. And make this explicit for them in your syllabus.

How did you come to education?

Education is a field that often attracts passionate advocates. Why do you get up every morning? What about teaching makes you come alive? Likely this relates to your own educational experiences (whether good or bad). You can let your students in on this story, too. Not only does it model for them the often non-linear ways we enter into our careers, but it can also build trust through your transparency. This helps students understand where you are coming from when you push them academically later on.

What is the connection between your work and the story of your students?

Audiences are selfish. No matter what you are communicating, no matter the topic, audiences want to see themselves in the content. So, where are you directly speaking to student experience in your syllabus? One way of touching the hearts and minds of students is to consider the framing of your class format, expectations, or purpose - finding ways to connect purpose, your story, and theirs.

As an example, here is what I write to my students under “Course Format”:

Welcome! :)

I recognize that you are sitting in this classroom for any number of reasons but whatever your path, know that I hope to help you on your journey. I was a community college student myself (and a GED recipient before that). Eventually, I made my way through the higher education system with the guidance of teachers, mentors and friends. I hope that, together, we can create a community in the classroom that supports your learning and sparks your curiosity. Thinking, reading and writing are activities you will do throughout your lives, and my aim is to support you in becoming the most powerful communicator you can be. Though I am a teacher of this course, I know that there is a wealth of talent, passion and expertise in my students that exceeds my own in many respects. For this reason, I also look forward to learning from you this semester.

How are you intentionally welcoming all students?

There are two key subtopics to think about when intentionally designing for inclusion and belonging:

Universal design:

I’ve spent a lot of time talking about visual design in this article. I want to be clear that it also is important to provide a syllabus that can be easily read by vision-impaired students and screen readers. This is why I always provide a Google-doc version of my syllabus with headings, subheadings and make sure all my images have alt-text descriptions, and never emphasize information through text color. This is not, by any means, the extent of what should be done in the pursuit of universally designed course materials, but it is a good place to start.

Culturally Sustaining and Responsive Design:

We live in a heterogenous nation, and many of our classrooms reflect a diversity of generations, nations, languages, races, ethnicities, and socio-economic backgrounds. This cultural wealth, this difference, can be leveraged for more enriching learning experiences, especially in the sharing of perspectives through discussion and writing. But this fertile soil of experience and expertise cannot be sown without intentional preparation in the early days of a semester. Here are additional statements to consider when putting together your syllabus to set the stage for community building in your course:

Diversity Statements and Land Acknowledgements: The syllabus is a crucial in making intentions and values clear to students. As such, I recommend including personalized diversity statements, land acknowledgments, and/or community/campus resource guides (that include ways to access free or low-cost mental health counseling, housing, food, textbooks, childcare, public transport, and emergency funds, if available). These statements should be from the heart, written in your voice, and explicitly state the ways you are designing the course to include all students to create learning that couples in high support with high challenge. Here is a good resource to start out with for diversity statements, and here is a template/sample for land acknowledgments.

Language choices and tone: Second-person “you” (to refer to students) and first-person “I” statements are more impactful than third-person writing (i.e., “the student will/the instructor will….”). Academic jargon can also be replaced by more straightforward or specific language (i.e., “learning objectives” → “What you will learn in this course”). You may also consider the ways in which language can encourage students to seek help; for instance, renaming “office hours” as “student hours” is one practice many instructors have embraced in this vein.

And, in the end, there is no perfection. I have tried all of the above in my syllabi over the years, watching the document change and evolve as my thinking, and my teaching approach, has. But I still return every year to re-engage with this task. In re-designing, I clarify what I feel is important about the work I do. I also signal the journey of mutual learning I’d like to take with my students over the next semester.

Moments of reflection are hard to come by as we put out fires in the first week. But I find taking the opportunity to turn a mundane task of cut and paste into a moment of intention, inspiration, and insight is always well worth the effort.

🔑 Key Takeaways

Syllabi often create unnecessary barriers for students through poor design, information overload, and impersonal tone.

Be aware of the 3 types of "user friction" - interactive, cognitive, and emotional - and target improvements in each area.

Use visual interest, chunking, and roadmaps to reduce interactive/cognitive friction.

Craft narrative sections carefully to increase transparency, belonging, and emotional engagement.

View your syllabus as a tool to motivate and support learners rather than just a repository of policies.

Start small: pick 1-2 friction points to address to create a more student-centered syllabus.

🖇 Resources from this Article

Free template for Powerpoint/Googleslide syllabus

Free template for Notion syllabus

Free template for Land Acknowledgements